Brazil is a country of many records. It is the largest country in Latin America and its largest economy. But hidden behind its prized modern cities and a matured tourism industry is a seemingly infinite green interior. It has the largest rain forest in the world, and on each inch of its growing corpse, the largest soybean production in the world that continues to expand by the day at the expense of the original peoples of the Amazons.

The land, then, needs hands to work on it. A significant amount of Brazil’s population are still peasants, the majority of them descending from African slaves – it is the country with the largest number of Africans outside Africa – and Indigenous people robbed of their land. They work in plantations, “latifundias” in Portuguese, the same word as the feudal manors of the 17th century under the Portuguese Empire. While these peasants today have access to the internet and cheaply manufactured American toothpaste, their living and working conditions remain the same. They work on a land that does not belong to them, crushed under suffocating usury. The majority of their harvest go to a small group of white landowners and representatives of US transnational corporations that have the State and its laws in their pockets.

The peasants are bound to the plantations in general if not one in particular. Unlike workers in the United States, they do not have the luxury of choosing their exploiters. For those whose entire possessions are taken from them by inherited debt, the only way to postpone certain death is to escape to the overflowing and starving favelas of the cities. There, the police launch genocidal waves of periodical incursions to “combat” the equally bloodthirsty organized crime, but mostly, the colored residents. After all, the words of the landowners are law, and to disobey them is to have serious consequences: sometimes it is being blacklisted from all sources of sustenance; some other times, if one is lucky, it is an arm. We shouldn’t forget that Brazil is the latest country in the hemisphere to abolish slavery in 1888, and just like in the postbellum American South, one form of absolute personal subjugation easily transforms into another.

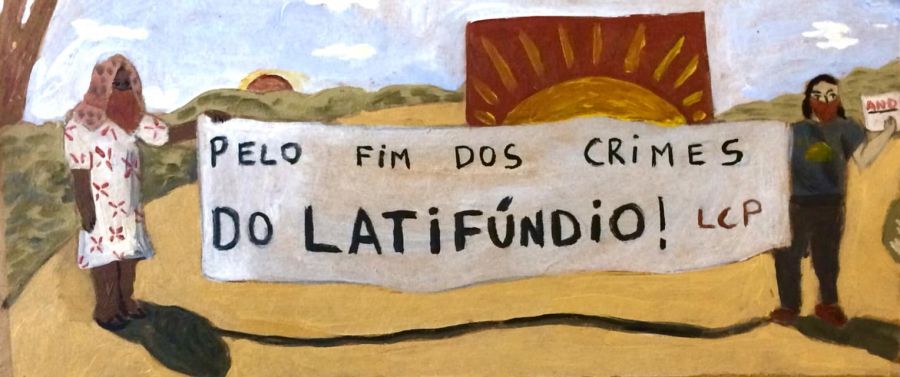

But Brazil sets another record: it is the country in the Western Hemisphere with the greatest revolutionary movement. Today, from the Northeast inland, where the maroons of old once resisted slavery, to the depth of the Amazons still being opened in the same way of Christopher Columbus, and to the far south of the country famous for the carnivals of Sao Paolo, the sons and daughters of those who once resisted continue to rise up in new conditions, under the banners of the League of Poor Peasants (LCP) and the Movement of Landless Workers (MST), with simple slogans: “conquer the land,” and “land belong to those who work and live on them.” To its participants, this movement is called “Agrarian Revolution.” The revolution does not just exist in slogans. All over Brazil, it is already being transformed into a new, warlike reality by the countless coarse, callused hands holding their machetes and muskets.

In the Renato Nathan Revolutionary Area, located in the interior of the beautiful coastal state of Alagoas, thousands of peasant families occupied large plantations and organized their lives according to their own wishes for 15 years. Production was collective and democratically decided, just like every decision made in the Area: people’s courts and people’s self-defense were set up, both concepts foreign to this broad land. Children receive education for the first time, organized by revolutionary students and workers from cities, on the Portuguese language, math, sciences, and the path towards building a new world without rich or poor. This is but one example of dozens of big and small revolutionary encampments across the country. The Brazilian people proved a Marxist law with their own experience: the masses create history, not a few selected individuals from the “talented-tenth” of the ruling-class.

In October 2024, the Renato Nathan Revolutionary Area was surrounded by the death squads of the landowners and the police armed to the teeth, accompanying a legal injunction made in the fancy courtrooms of the bourgeois-feudal State. For 15 years the peasants fought for their continued existence; but this time the enemy came more prepared than ever and their homes and fields were razed to the ground in a matter of days. Shortly after, another encampment in the State of Sao Paolo was violently raided, 3 peasant leaders killed by the reactionary gangs. This is another Marxist law: there is no empty room in this rotten society of exploitation for revolutionaries to take advantage of. The enemy will sniff out and destroy every attempt to “build bases” or “accumulate forces”, and every inch of free space will have to be taken from the hands of the enemy.

Two months later, the Renato Nathan Revolutionary Area was taken back after an intense battle against the military police. In front of the barricades, the class enemy ran away. The peasants began to rebuild what was destroyed, red flags and a banner depicting Zumbi dos Palmares – the greatest hero of the Quilombolas (maroons) who defended his settlement for 67 years against Portuguese slavers – were among the first things to be erected again on the land. Here we again witness a Marxist law: everything is lost and gained in fierce class struggle: if the working class doesn’t impose this struggle against its enemy, it is imposed against the working class. In a society enforced through reactionary violence of the few, the highest form of class struggle is revolutionary violence of the many. Indeed, it is the only way to sweep away the Old Society everywhere, from a single plantation to any given country in the world.

Similarly, the Brazilian peasants are not merely won over by propaganda, studies, and community events operating under the legal bounds of the Old Society. In tens of thousands, their ties with each other were baptized and tried in their common struggle, in the blood and tears they have shed together, and in their collective strength they have demonstrated with each plow and each bullet. A quote from the Peruvian revolution, borrowed by the Brazilian revolutionaries, is befitting here: may the actions speak. The actions have spoken, not words, and it is in this way the revolutionary movement grows by the day and reaches the most remote corners of the countryside and cities.

The Brazilian revolution is relatively less known among Black workers and intellectuals in this country. Equally less known are its lessons, particular in form, but universal in essence. The story of Zumbi dos Palmares is the same story as the story of Nat Turner, who took up the highest form of struggle. Let us look at our own history, going back all the way to the first slave rebellion in continental North America in 1526. After that, the Stono rebellion, Nat Turner’s uprising. The Civil War itself was fought through the mass struggle and war of the enslaved Black masses, as African slaves were both joining the Union Army en masse and forming militias to annihilate the southern plantation-owning class.

Looking at the contemporary Brazilian peasants, we can’t help but be reminded of the struggle of our sharecroppers in the 1930s. Under the leadership of Communists, there as well as here, the Sharecropper Union responded to the white landowners enforced by the police and the Klan with guns in hand, not merely resisting under these harsh conditions but taking the offensive through combat: every single struggle built up and paved the way towards the confiscation of landed property through revolutionary violence. Just like in Brazil, they rejected the Manichean separation common among the nationalist movement today that draws a Chinese wall between first resisting and then combating, first passively ensuring survival and only then recuperating the strength to struggle. The December 1930 issue of The Southern Worker, an organ of the Communist Party, featured this quote from a Black worker: “[W]e workers here have seen fight… but because we lost, then, doesn’t mean we will lose again. We must organize, the white and Negro workers together from the very beginning, or the bosses will use one race of workers as scabs against the other in order to break the strike. We got to organize and fight real.”

The Brazilian people’s struggle is centered on agriculture and it is from there that originates the phrase, “Agrarian Revolution.” Taking land has a concrete economic and social significance: agriculture is what a plurality of the population engages in, what takes up a majority of the territory, and what constitutes a significant portion of the country’s economy. As the peasantry flock to the cities, similar semi-feudal relations, dependent on personal subjugation, are recreated and maintained in the cities as well. A struggle to transform the countryside and agricultural production is a struggle that frees the land and the people, a struggle that destroys the pillar of society that the capitalists and landowners depend on.

The situation in the United States is different. The majority of people in the United States, the Black nation included, today reside in cities. Most people in this country are workers and the economic arteries are industry and logistics. To learn from the lesson of the Brazilian revolution is to have a concrete analysis of the concrete situation. Today the industrial proletariat and especially the Black industrial proletariat are the ones with the centralization, closeness to the mechanisms of capitalist production and united prospective that they are the class with the historical task of overthrowing the capitalist class and building a New State. They have the historical task to lead the socialist revolution because of their closeness to the mechanisms of capitalist production, by taking active part in the production and distribution of commodities. We cannot be dogmatic in our analysis. Clearly, our revolution, although with a national character, is not a Democratic Revolution, but a Socialist one. The Black workers have been long familiar with the mechanisms of capitalism. The answer is not to resolve the agrarian problem or to develop a separate Black capitalist class: it is to organize the majority of the population wherever they work and live, to seize the factories and shops that we already work at. It is also here that Black workers alongside their white and Latino coworkers will deal a decisive blow to the imperialist Power structure.

Instead of simply raising awareness on the national problem, the masses’ day-to-day issues must be addressed just like in Brazil: through militant and class-conscious struggle against the class enemy, as the only way to grow our ranks towards developing the highest form of struggle, the struggle for State Power.

In Brazil as well as here, the society is divided into two. There are two main forces: the exploiter capitalists and the exploited working class and their allies. There are two roads and two destinies. First, the road of the ruling class, that continues its genocide against oppressed people here and across the world and continues the capitalist system built on human suffering. Second, the road of the working class, the road of creating a new world with no exploitation and oppression, that place the ownership of the society in the collective hands of the great majority of workers who already work and live in the most collective way possible.

This is the way forward demonstrated by Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, the guiding ideology of the Brazilian revolution. Walk the path of the Chinese! This is the answer. This is not a conclusion came about lightly, nor is it unique. The Mozambican, Nigerien, Peruvian, and Filipino people reached the same conclusions after years of long and intense class struggle in the form of People’s Wars.

The Brazilian peasants understand that there are not many Communisms. There is one reality and one truth, drawn from the history and practice of the working class of all countries, and all oppressed classes before it. At the same time, the experience of each nation and people, through studying and applying the universal ideology of the working class, not only particularizes it in each country but enriches it overall towards the further development of Marxism. This is especially important for Black workers in the United States to understand. As our exploiters are the same ones that today enslave all oppressed people of the world, we are fighting in different trenches of the same World Proletarian Revolution, sharing one destiny and on the same road toward the victory of luminous Communism.

There is many more that can be written about the struggle in Brazil. But for brevity’s sake, let us “return to the source”: we look to Brazil for a reason beyond simply gaining more knowledge of what’s going on in that corner of the world. Only by grasping these lessons, as the revolutionaries of Brazil have will we be able to reach the heights our struggle requires. Only then can we retake the heights of the slave revolts before and during the Civil War, the heights of the 1970s, and especially, the heights of the struggle led by the Communist Party in the early 1930s: in fact, we need to go above and beyond the past efforts. We must walk the path lay forth by Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, a revolutionary tradition of not only our people, but the whole world’s proletariat and oppressed classes. The Black Nation has struggled and will continue to struggle but it is up to us as revolutionaries to mobilize, politicize and organize the masses into struggle for a new society and for the liberation of our Black Nation.

Leave a comment