In 1956, the West African poet David Diop wrote these powerful words in the pages of Présence Africaine:

We know that some people wish to see us abandon militant poetry (a term that makes the “purists” sneer) in favor of exercises in style and formal discussions. Their hopes will be disappointed because for us poetry does not come down to ‘training the language animal’ but to reflect on the world and to keep the memory of Africa.

Like the splinter in the wound.

Like a tutelary fetish in the center of the village.Only in this way can we fully exercise our responsibilities and prepare the renewal of our civilizations.

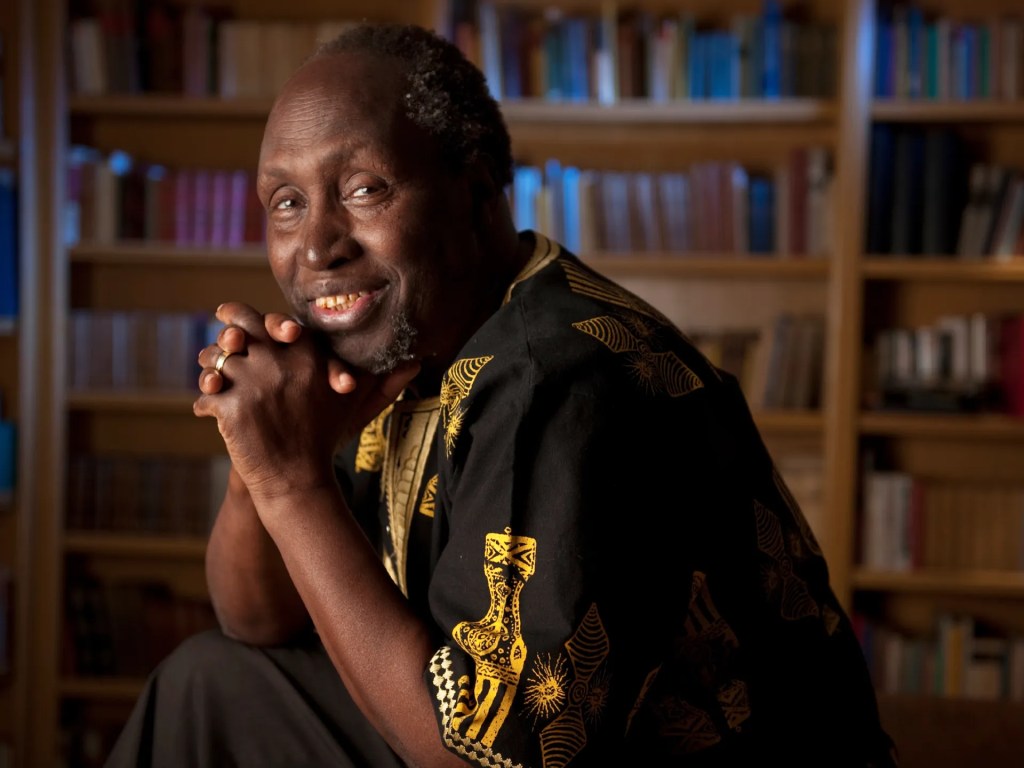

This short paragraph encapsulates the life and work of the Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who recently passed on May 28th, 2025.

Ngũgĩ was perhaps most well-known for his numerous international prizes. In fact, he was often considered a likely candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature. But Ngũgĩ was more than just one of the most important literary figures in contemporary Africa – a place he nonetheless rightfully deserves. He was many things at once: the sibling of a victim of British colonial violence; a political prisoner under the fascist Moi dictatorship; a friend of the poor peasants in their struggle for land; an inheritor of Bertolt Brecht and the curator of the first revolutionary theater in rural Kenya. He was a professor, an exile, and a Communist revolutionary of the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist tradition.

Born in 1938 in colonial Kenya, Ngũgĩ came of age during the Mau Mau uprising, an experience that would deeply inform his critique of imperialism and class oppression. Initially writing in English and gaining international acclaim with novels like Weep Not, Child and A Grain of Wheat, Ngũgĩ began writing exclusively in Gikuyu, his native language, since the 1970s; arguing that language is not just a medium but a weapon in the struggle for decolonization.

For Ngũgĩ, literature comes from life but is higher than life. It serves to reflect reality; to uncover and preserve the history and struggle of those seemingly without history, those whose societies were uprooted from their natural development, disrupted and malformed by the bloody crimes of colonialism and imperialism. At the same time, it is a weapon to direct and serve the revolutionary transformation of reality, for the proletariat and its allied classes to shake the world upside down and to create everything anew in their image, rooted in the fertile soil of Africa’s living culture which has stubbornly defied all attempts of “civilization.” In his own words, the role of literature is to “decolonize the mind.”

He carefully used his words, with little garnishment, to evoke clear images and emotions to keep the memory of Africa, to fully exercise his responsibilities and to prepare for the renewal of our civilizations. He navigated, took apart and pieced together in a higher form the local, tribal, national, and universal identities across the continent through the masterful use of language. Common themes in his work include an entanglement of flashbacks, violence, and magic sometimes indiscernible from reality, like the story of so many in the age of strife that had befallen his homeland of Kenya and of Africa as a whole in the crossroad of colonialism and decolonization. Like the story of the violent and brutal rule of the white man who transplanted a foreign system onto entire peoples and of the seeming independence, the blood shed in vain, the replacement of white claws with native African ones under the national flag, the confusion, betrayal, and agony with the deepening of bureaucrat capitalism that plunges the continent into an ever-worsening crisis. Like the story of his own brother, who was killed by the British for not listening and obeying to the order to stop at a checkpoint due to his own deafness and him who was thrown into the prisons of the supposed heroes of independence; like the story of Kihika, and then, of Kĩgũũnda.

Ngũgĩ did not stop at interpreting the world, like so many acclaimed intellectuals mired in the post-modernist tradition, who present a picture of “noble savages” for the imperialist metropoles, or like those who indulged in symbols of the fleeting past as a static dogma. He was Ngũgĩ the revolutionary, who sat on the Central Committee of the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist December Twelfth Movement,pointed out with unmatched clarity the primary contradiction between imperialism and the oppressed nations, the main task of agrarian revolution, and the path of New Democratic Revolution through Protracted People’s War; uninterruptedly passing to Socialist Revolution until achieving shining communism. It was towards this goal that he dedicated all his effort.

Ngũgĩ has lived many lives, but like Chairman Gonzalo (whom his organization once stood in solidarity with), he did not live to see the victory of the revolution and the end of neocolonial domination. Today, Africa, like her diaspora in the Americas, continues to live in poverty and crisis, with no real alternative appearing on the horizon. From this the lack of revolutionary alternative, many pretenders have risen to take place as false liberationist, just like Jomo Kenyatta more than a half century ago: a petit-bourgeois nurtured by imperialist education, desperate in its fin de siecle spirit, reaches out for an abstract idea of freedom with no clearly defined path to get there. Meanwhile, the masses, throughout the diaspora, are clamoring for change, for organization, for struggle. Especially worthy of note is Ngũgĩ’s own homeland, Kenya, which has seen nothing but more imperialist plunder with the passing of each year; which is rising up in fierce and heroic armed resistance as these pages are being written. It is then appropriate to close this obituary with the concluding line in Ngũgĩ’s famous work, Decolonising the Mind:

[This book] is a call for the rediscovery of the real language of humankind: the language of struggle. It is the universal language underlying all speech and words of our history. Struggle. Struggle makes history. Struggle makes us. In struggle is our history, our language and our being. That struggle begins wherever we are; in whatever we do: then we become part of those millions whom Martin Carter once saw sleeping not to dream but dreaming to change the world.

Leave a comment