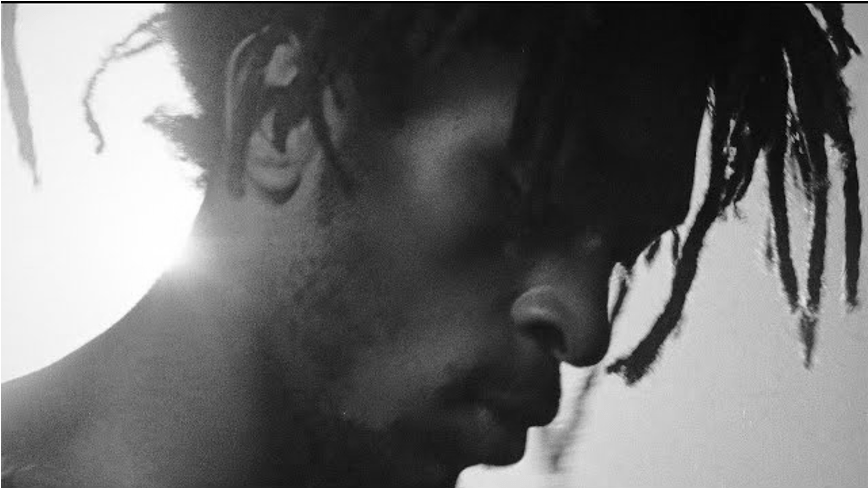

We interviewed North Philly rapper Ghais Guevara about his new album Goyard Ibn Said, creating Black Art, and looking towards the future as Black people for The Crusader. His art consistently pushes the limits of hip-hop as he deftly critiques imperialism and colonialism while exploring the deeply personal.

Crusader: First off, we wanted to know how you navigated that transition between There Will Be No Super Slave and Goyard Ibn Said? What kind of mindset did you go into the new album with?

Ghais: At first, it was kind of like an “I wanted to showcase versatility” thing, but it became narcissistic. Like pretentious – I don’t know, trying to act like there’s this barrier between different types of hip hop, as if one can’t be appreciated alongside the other. So, I kind of just decided to group them all into one cohesive showcase instead of a mainstream versus underground thing, and it ended up becoming something that’s more of a spectrum than, you know, two different sides.

C: Right, especially because people are convinced that there has to be a dichotomy.

G: Yeah. It was just weird being the human that existed between the planes, you know? So, it didn’t make any sense to just keep it as if I had to pick a side.

C: On this album, you were kind of experimenting with production. What type of influences did you draw on?

G: It really depended on the song or how I wanted to approach it. Like, a lot of 808s. On Camera Shy, I would listen to a lot of Chief Keef’s beats and how he would mix his shit. It’s just kind of scattered all over the place, random books that I was reading at the time and things that I just thought contributed to the theme of the album overall.

C: What were you reading?

G: The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. And I was big on Persona; the movie you know the Ingmar Bergman film? And you know, just big on a lot of early 2000s rappers and their lyricism and how they approached their shit.

C: With the rollout of this album, do you feel like there was something kind of under-acknowledged or glossed over in the way people approached it?

G: Yeah, I do definitely think people weren’t really paying attention to the fact that there is a core story there… I’m seeing complaints about, like, Luke’s involvement in the album – same complaints. They simply don’t understand the album. It’s like, well, I’m kind of telling you, literally. But other than just people outright not putting that effort in, I don’t think, nah. I think pretty much everybody came to the similar conclusion that I wanted to present with the album.

C: I guess when it comes to art, you can’t really predict the reactions.

G: Yeah, sometimes you’re just too distant from a culture to really get it. I’m learning that sometimes, if you just don’t get it, you’re not there yet. You know, I’m out in Europe, I’m seeing some shit, and I’m just like, I don’t get it yet, I’m not there yet. Maybe I will in the future.

C: Since you’re in the UK right now, what are your thoughts on the interactions of Black people in the diaspora? Or what kind of lessons do you think we could probably pick up on?

G: In my experience, a lot of the diaspora folks over here are very much looking for an outlet. I guess that’s just the nature of my career though, making music and shit. A lot of us don’t mind living for others, living through others. You know what I mean? There’s a thing of that “non-individualism” amongst all of them, and just no place where they can have that individualism just for a little a bit. I think they all feel a bit hassled, a bit overworked.

C: How is it being with other Black people who aren’t American?

G: It’s not even a fair comparison, because I spent the majority of my life in America, in impoverished neighborhoods, undereducated neighborhoods, so on and so forth. And over here, where I live at I’m in better places, better spaces, you know? It’s still that thing of, “if you know, you know.” I still kind of feel at home, so to speak. That’s why I never get the differences, other than the surface level ethnic and linguistic differences and all of that.

C: If you had to think about how your art functions in service of Black radical thought – not to say that that is what your music should be, but when you’re reflecting on it – how do you feel about how it intersects with revolutionary action?

G: If I’m being honest, the answer is always going to be more intangible than physical. I think the closest material means you can get is from an individual sense within your community and from a financial sense. But once you get into an organizational sense you can’t, you can’t balance that industry, you know. I wish it was a world in which you could be more directly impactful. And I think now, with the more direct consumer ways that we’re consuming music, you can do more of a impactful giving back thing strictly from your music. Your proceeds can go to this and can be tied to this and fund things. There’re ways, especially with the internet, but definitely as of now, the answer is probably, you know, the same old, lifting people up, giving them hope [laugh].

C: People already figure that, being a Black artist, your work has a political tinge to it. With that in mind, do you feel like that ever significantly impacts your writing process?

G: it used to definitely. I used to force myself to be like, ‘I gotta have something to say.’ But at a certain point you just realize that’s like the cop in your head. You know, it’s a pretty narcissistic trait. Nowadays I’m kind of letting it come to me. You know what I mean, how close it is to home or whatever. I don’t have to really chase tragedy. It’s not something that I really force now, but definitely I used to.

C: We’re kind of looking at a more explicit rightward shift worldwide. What are some things standing out to you the most?

G: It’s one word I’ve been saying over and over: cannibalization. It’s like people are just doing, growing, expanding, getting greedier and greedier. And then shit is like, oh, it’s no more. And then they’re like, oh, shit, I spent so much time chasing instant gratification that I didn’t spend my time preparing for when that shit runs out. I be seeing that across industries, across people with themselves and their health and how they’re treating themselves, I think we definitely have reached the thing of rushing towards glory and not understanding that it takes time. It takes each other.

We’ve created a system where the people that that grew up not having to recognize that; You know what I mean, the Elons, the Trumps, they grew up in their shit. We’ve opened the door enough for them to literally sit there and be the rulers.

C: How was it growing up being taken along to rallies and protests, etc?

G: Yeah, I went to a bunch of MOVE rallies, for Mumia [Abu-Jamal] and all that. It makes you so much bolder. It’s kind of weird thinking – being that young and already thinking your above authority [laugh] and just abusing it. And it’s kind of weird, because children are, at the same time, they are an oppressed class. Like, definitely children are the most oppressed, but at the end of the day, people that value their kids, they know the kid is the fucking boss, like we have to figure out how this works around them, type of shit. So I was given a lot of room. You know, it helps to be that way. It’s always times to be bold, it’s always time to be louder and to question something. At a certain point you realize you can’t fight everything. And, you know, fight every battle and start every argument. It’s just like you gotta let people be stupid.

C: Does it help you articulate your positions whenever you need to?

G: Yeah, definitely. I mean, joining those helps to have those conversations forever. And then it loads up for later. That’s what I think a lot of people don’t understand about talking to me, is – well, that’s what I had to figure out about a lot of people. A lot of us are literally just making it up as we go. So being able to have that ammo, because we’ve done it so many times, and they had those conversations so many times, definitely helps.

C: How do you bridge that gap (even though it’s usually not a big one) between being more politically aware all your life, versus folks who weren’t on that type of time?

G: I mean, I love meeting people where they where they’re at, I love when a person doesn’t understand. Sure, let me explain, give me the reassurance that you’re trying to meet me where I’m at. So, you know, I don’t see the incentive in being condescending. It’s only reserved for, like, showing off, but it’s really no purpose in everyday life.

C: Are there any texts you would ask other Black people to try and pick up in this climate?

G: Oh, I forgot to mention – Black Skin, White Masks. That was another big influence. I think that’s a big one, because we’re coming to a point I think a lot of Black people, I was talking to FARO, I think we as Black folk, have finally fought ourselves to the point where we are allowed to think about our existential existence beyond, like, certain types of oppression. It’s just more and more well-off Black folk now It’s producing certain kinds of communities and shit like that. You know what I mean? Sons of rappers and sons of ball players, and they’re going out and they’re having their experiences, their fun. It’s fucking loaded. It’s not the same anymore.

C: It’s wild when you meet Black people who only have class aspirations.

G: It’s slipping into more and more of us having those actual identity crises. I just think the book really does do a good job at, like, dialing it back and just understanding where certain things come from. That [book], Dubois, The Souls of Black Folk too. I think it’s big on that too. Yeah, powerful shit.

C: Thank you! Is there anything you wanna end on?

G: I’m supposed to be doing a mixtape soon, I’m very excited about it.

C: When is that coming out?

G: Um, I don’t know. [laugh] They want me to do a couple songs first, then we’ll figure it all out. I want to have some summer songs.

Leave a comment