We republish this article from Brazilian democratic and revolutionary newspaper A Nova Democracia (The New Democracy in English). Founded by a mix of veteran revolutionaries from the 1970s, worker and peasant leaders, as well as progressive intellectuals, A Nova Democracia has been the leading voice for the Brazilian revolutionary movement for more than two decades.

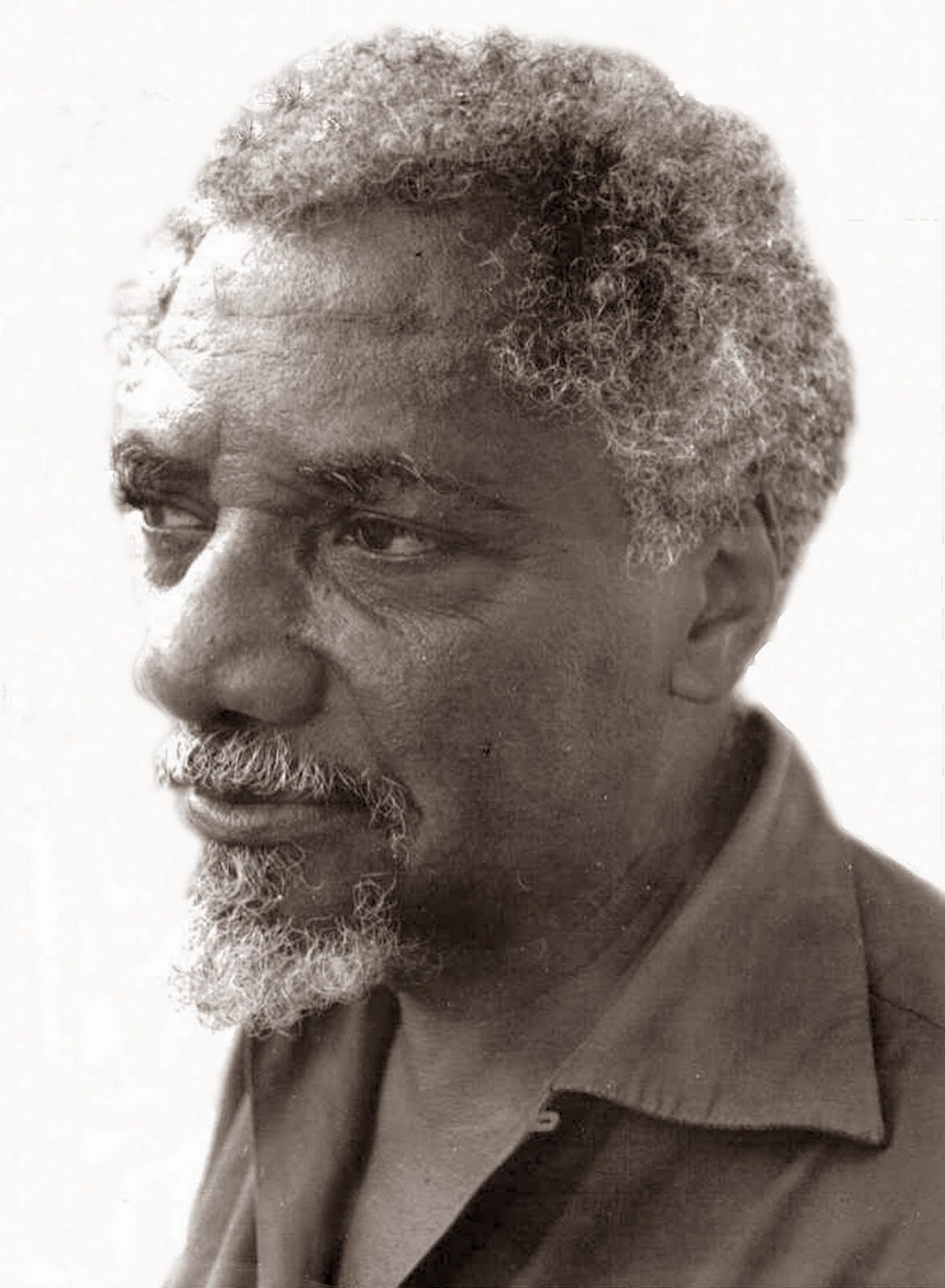

Solano Trindade was a communist militant, poet, painter and theatrical artist. He opposed social and racial injustice and loved the arts. His story is intertwined with the artistic vocation of the city of Embu das Artes. His daughter, Raquel Trindade, who continued his work, tells us about his career, which is intertwined with her own. And vice versa.

Born in Recife in 1908, Solano learned to dance Pastoril and Bumba-meu-boi from an early age with his father, the shoemaker Manuel Abílio. With his mother, Emerenciana, a baker, he began to read cordel literature and romantic poetry. However, unlike his parents, Solano was revolutionary for his time.

While still living in the Northeast, he took part in black cultural movements, such as the First and Second Afro-Brazilian Congresses in 1934 and 1937, organized and proposed by Gilberto Freire, and in 1936 he created the Pernambuco Black Front with José Vicente Limas, Barros Mulato, and a few other comrades of the time. The Front was aimed at the anti-racist struggle and the search for African cultural roots.

After publishing some poems, he began his pilgrimage. He traveled to Minas Gerais and then to Rio Grande do Sul, where he set up a Popular Art Group.

But Solano really left his family in the northeast to try life in Rio de Janeiro. Raquel, his daughter, tells us:

“After he left, Mom thought he was taking too long, and we came by ship after him. She only knew that he met at the Vermelhinho [bar and café], which was opposite the Brazilian Press Association, she went there and Grande Otelo said: “he comes here every day, in the afternoon”. He welcomed us as if he himself had sent for us. His friends raised money and he rented a rooming house in Rua do Livramento, in Rio de Janeiro, in Gamboa.”

Political activism

Vermelhinho was a place where young left-wing artists, poets, intellectuals and journalists gathered. There he was friends with people like Barão de Itararé and Santa Rosa, Aníbal Machado, the writer Eneida … Raquel remembers them discussing the Second World War, the Soviet Union, Stalin and Trotsky.

In the 1940s, Solano Trindade joined the Communist Party. Shortly afterwards, he and his family moved to the city of Duque de Caxias, in the Baixada Fluminense. He belonged to the cell Tiradentes, which functioned in his own home, where peasants, intellectuals and workers gathered. Raquel remembers this period of his militancy:

“He had tasks that the party passed on. There was a lot we didn’t know. There were Prestes’ birthday parties. There were the rallies, there was the time of “O petróleo é nosso” (oil is ours), I even helped to collect signatures, there was a time later against the atomic bomb. There was a lot I didn’t know, but I was a young girl and I wasn’t connected yet.”

Cast of the Teatro Popular S. T.

Solano was arrested twice, once in Niterói and again during the Dutra government’s communist persecution, when he lived in Duque de Caxias. Raquel says that the police arrived and her brother, Liberto, was sick with measles. The police turned over the mattress with the boy and everything to see if there were any weapons.

“They took him into custody. At first we thought it was because of the poem (Tem gente com fome), but now with a survey at Dops I found out that it was a complaint, from a person who lived in the vermelhinho,” says Raquel. Mother and daughter went through all the prisons to find their father, worried about torture. They found him and he wasn’t tortured.”

Solano left the party because he believed that the problem of black people wasn’t just economic, it was also racial. He believed that poor people also needed to have more access to culture and the arts in order to have equality “We will not fight racial battles, but we will teach our black brothers and sisters that there is no superior or inferior race and what distinguishes one from the other is cultural development. These are legitimate desires that no one in good faith can refuse to cooperate with,” said Solano.

Solano died a socialist, but outside the party.

Art of Solano

As well as painting and writing his poems, Solano was also a militant of the arts and fought hard to ensure that popular and folk art was widely disseminated.

Shortly after arriving in Rio de Janeiro in ’45, he set up the Brazilian Folkloric Theater with his wife and Haroldo Costa. By this time, Solano’s paintings had been sold internationally in group exhibitions and one of his books had been published, Poemas d’uma vida simplesn . The “Brasiliana” group left the Folkloric Theater with the Polish director Askanasi, a dance group that became famous for numerous performances abroad. However, with the director the group lost its authenticity, the folkloric traditions were stylized and Solano decided to leave the group and form his most important and successful movement, the Brazilian Popular Theatre.

Although it didn’t present plays, it was called a theater because “it encompassed plastic arts, literature and dance and because what the people do is a theater, it’s a popular theater, that’s why it’s the Brazilian Popular Theater,” explains Raquel. Created by Solano, Margarida Trindade and sociologist Édson Carneiro, the TPB performed readings of dances such as maracatu, lundu and bumba-meu-boi. It was made up of maids, workers, students and teachers. They rehearsed in Rua da Constituição, in Rio, when it was formed in 1950, but soon moved to Duque de Caxias.

With TPB, Solano went to Eastern Europe in 1955. They toured Poland and Czechoslovakia in 21 different cities. He took part in the International Popular Dance Competition and performed to an audience of 5,000.

Embu of the Arts

Back in Brazil, at a performance in São Paulo, he met the sculptor Assis, who already lived in Embu and invited him to come to the city. Solano fell in love with Embu and took the whole cast there.

“We had a three-day party, dancing in the streets, painting, which began to attract tourists from all over the world. And today Embu is Embu das Artes (Embu of the Arts) thanks to my father” – says Raquel.

Ever since Duque de Caxias, he wanted to create a city dedicated to the arts and he succeeded in Embu. The craft fair came later. Together with Solano, the artists from Embu had started a movement in Praça da República in São Paulo in 1966.

“We’d go there in the morning and come back to Embu in the afternoon – Raquel recalls – so Assis was worried that the movement there would hinder tourists coming to Embu. This was the start of the craft fair in Embu. We’d go to the Republic in the morning and come back with the rippies from the 60s with their handicrafts, and then it broke out in ’68, ’69. Dad’s group danced in the streets, we painted…”

The Brazilian Popular Theater continued to perform in colleges, on the street, in almost all the theaters in São Paulo at the time and many across the country. Always with a large audience, according to Raquel Trindade. When Solano died in 1974, Raquel Trindade created the Solano Trindade Popular Theater in 1975 to continue his work. She continued the path of knowledge, passing on cultural and folkloric traditions from father to son, which are now even found in Raquel Trindade’s grandchildren.

For Raquel, her father’s greatest social contribution was to help preserve popular culture and all his work for black people’s self-esteem, to make them stronger.“But it’s not just for black people, it’s for all ethnic groups. There was a phrase of his that we still use today: ‘Research the source of origin, give back in the form of art’“ – adds Raquel.

Leave a comment