Juneteenth was made a federal holiday in 2021, and yet Black people in America continue to struggle against the exploitative and oppressive system this country was built on. We will discuss a brief, non-exhaustive history of Juneteenth, especially as it pertains to Texas, and explore what lessons this holiday has for us as revolutionaries today.

The Civil War & Emancipation

After Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States in 1860, several southern states decided it was time to secede from the Union. The Republican party’s anti-slavery platform had already been unpopular with the 11 southern states that had no intention of abolishing slavery, and by 1861, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas seceded in that order (PBS). Later that same year, the forces of the newly formed Confederacy attacked Fort Sumter, tipping the country into civil war. Two years later, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all enslaved Black people in Confederate territory would be freed if the rebelling states did not surrender.

This outline of events sounds straightforward, easy, familiar – but it needs an innumerable number of caveats. Pushing back against the idea of Lincoln as a kindly Great Emancipator is hardly controversial these days. One of the most well known examples of his general position is in his response to abolitionist Horace Greeley’s criticisms in 1862:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do, it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” (Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum)

A more honest examination of Lincoln, and more generally, Northern “anti-slavery” attitudes shows that they mostly happened to coincide with the region’s economic interest. After building industrialized cities on the backs of slave labor, the capitalists deemed slavery largely unnecessary. The agricultural economy of the South, on the other hand, was dependent on this continued exploitation to keep running (Secession in the United States: EBSCO) Ultimately, Lincoln worked in the class interests of the North: without slavery, the Confederacy would not be able to keep up the war effort (PBS).

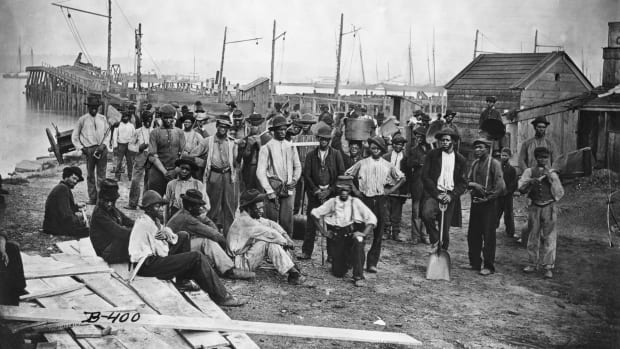

Up until the Proclamation was declared, the federal army did not formally accept Black soldiers. As DuBois points out in The Economics of Negro Emancipation in the United States, “So far as the great mass of people in the United States were concerned, the war had begun with no thought of emancipation…[b]ut after about two years of this the white men were glad to accept 200,000 Black bodies to stop bullets.” Black men enlisted in droves when finally accepted – by 1865, over 186,000 of them had joined the army, half of which were from Confederate states (PBS).

Inevitably, the army took every opportunity to subjugate these Black troops. Black soldiers were initially paid as laborers instead of soldiers: they were paid $7 per month while white soldiers, by comparison, were paid $13. Today, this would roughly be equivalent to $220 per month for Black soldiers versus $408 for white soldiers (Consumer price index, 1800-: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis). In response, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Colored Regiment, the first all-Black unit in the army, served a year without pay, and many other Black people refused to enlist outright. Finally, equal wages were sanctioned for Black soldiers in 1864.

In the midst of all this, the masses were hit by wartime scarcity, primarily in the South. While Northerners faced inflation and some labor shortages, those in the South had to fear the looming threat of starvation. Besides a drought in 1862, Southerners were unable to exploit Black labor to the same inhumane degree on their plantations for food. This brings us to Texas, one of the last strongholds of chattel slavery in the country.

Galveston, Texas, and the U.S Today

While Black people throughout the North celebrated the Proclamation soon after it was declared, it took much longer for the news to reach enslaved people in Confederate states. Up until 1821, slavery had not been established as an institution proper in Texas when it was a Spanish province. White American settlers received eighty acres of land for every enslaved person they brought into Texas: by 1825, enslaved people made up about 25% of the population in Austin (Campbell). Of course, these settlers’ primary motivation was to make as much money as possible from cotton plantations. Through slave labor, cotton economy strengthened and entrenched slavery in Texas and became the most important commodity in America in this century.

Throughout this period, about 3,000 to 5,000 slaves fled the clutches of plantation masters to Mexico, which maintained a general anti-slavery stance upon its independence and refused to return fugitive slaves back to slaveholders (Burnett). However, despite slavery being illegal to different degrees since 1823 in then-Mexican Texas (i.e. the State of Coahuila and Texas), several leaders helped colonists circumvent and gain exemption from anti-slavery laws.

Capitalist slaveholders of the antebellum era dominated white society and made millions as the century went on while ensuring Black people had no legal rights or basic freedoms. Despite their conditions under the Slave Codes, which need no retreading in this piece, enslaved people resisted in many ways throughout this period. Often, they disrupted the plantation system: they “slowed down their work pace, disabled machinery, feigned sickness, [and] destroyed crops” (PBS). While there is no record of an organized rebellion in Texas, there are instances of instances of individual enslaved people violently revolting against slaveholders (Campbell).

With enslaved people making up much of the population and outnumbering the ruling class of slaveholders, virulent anti-blackness, and the Civil War brewing, white plantation owners lived in constant fear of a slave insurrection in the mid-1800s. It is worth pointing out that Texas was surrounded by anti-slavery sentiment from all sides, even if the sentiment in question lacked any real backbone. As mentioned earlier, there was the Union to the North and Mexico at their southern border, but even the deeply imperialist nation of Britain refused to recognize Texas as an independent nation due to its reliance on slave labor (Burnett). Slaveholders in Texas were incredibly defensive about their “peculiar institution”, and created a sense of social panic so all-consuming that they blamed a series of fires in North Texas on a group of enslaved people and abolitionists in 1860. They took the opportunity to hunt down and hang at least 30 people for this conspiracy, even though there was no evidence that these fires resulted from a planned slave uprising (“1860: Big Trouble”).

Against this backdrop, General Gordon Granger landed in Galveston with Union forces to occupy Texas on June 18, 1865 – 2 months after the Confederate army surrendered in Virginia, and 2 years after the Emancipation Proclamation was first declared. The next day, Granger issued General Order No. 3, officially stating that all enslaved people in Texas were now free.

In Limestone County, TX, a slaveholder named Logan Stroud cried as he read out the proclamation to the 100 Black people he had enslaved to build an empire of over 11,000 acres (Bell). Newly freed Black communities in the area started celebrating their emancipation began as soon as 1866, with festivities in the outskirts of town (Acosta).

Then, in 1892, 89 Black people bought acres of land in this same country to create a permanent site for Juneteenth celebrations that were “like a giant family reunion, held on hallowed ground” (Hall). The community formed the Nineteenth of June Organization, one of the first official committees created for this holiday. They have hosted the longest running Juneteenth celebration in the country at that same site, now called Booker T. Washington Park (Wilson).

Similar acts of remembrance spread throughout the state and to the rest of the country. Juneteenth had already been celebrated since 1867 in Austin with the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau, but the first purchase of land to celebrate emancipation was made in the early 1900s by the Travis County Emancipation Celebration Association (Acosta). Black people also took the tradition to other states during the Great Migration, yet it is also worth noting that Black people in other states had been celebrating their emancipation on different days due to how staggered the actual process of emancipation was for enslaved Black people. For example, Black communities in Tampa celebrated an Emancipation Day in May, to commemorate the arrival of federal troops on May 6, 1864 (Cimitile).

Attendance at Texas celebrations grew throughout the 1900s and often featured storytelling from elders about their experiences during slavery, prayer, dances, and games (“Texas observes Juneteenth”). This was an event everyone in the community looked forward to as it felt like a county fair, with people hitching rides with each other to head to the park and buying fried fish, popcorn, and homemade ice cream from concession stands (Hall).

Juneteenth celebrations have also been historically used political rallies and to educate Black people on their rights and history. In Mexia, Limestone County, the Emancipation Proclamation was read out every year along with the names of the founders of Booker T. Washington Park. More recently, the celebrations have commemorated the somber memory of the Comanche 3, three Black teenagers who drowned in police custody in 1981 – Anthony Freeman, Carl Baker, and Steve Booker.

As this tragedy highlights, Juneteenth and the process of emancipation did not eradicate the anti-blackness in the fabric of Texas and of the United States as a whole. The history of these celebrations occur against the backdrop of the brutal sharecropping system at the beginning and continue through Jim Crow and segregation. As DuBois writes, “the slave was emancipated without being given a foot of land or a cent of capital.”

A Juneteenth for the People

The experiences of Black people throughout U.S history continue to demonstrate that this country only makes concessions that reform capitalism to fit the era and not to serve the interests of the Black masses.

It took until 1980 for Juneteenth to become a state holiday in Texas, its own birthplace, and until 2021 for it to become a holiday nationwide. We must question the ultimate usefulness of any formal recognition of Black history, especially when Black communities have been honoring traditions without any need for official sanction. What does a broad acceptance of Juneteenth as a day off of work mean when we have been seeing capitalist institutions co-opt and water down the ideas behind Black movements for years?

While the ruling class continues to accumulate wealth at the expense of the Black masses, they enlist the repressive power of the police state to protect themselves and further debilitate Black communities. Black schoolchildren struggle to get access to the education they need to succeed in a country that seeks to constantly undermine their future. The extent to which this system strategically attacks Black freedoms cannot be adequately summed up here. The need for liberation remains urgent.

On Juneteenth, instead of accepting an imperialist country’s efforts to placate the nation it oppresses, we can instead look to the efforts of the Black people who paved the way for us to continue the struggle today. Enslaved Black people did not wait for emancipation before choosing to sabotage slaveholders’ plantations or establish routes to help their people flee. Black people today cannot wait for the institutions that dehumanize them to somehow hand them to keys to their freedom. To achieve true liberation, we are tasked to end this capitalist system and the oppression that feeds it, and we can settle for nothing less.

Leave a comment